Solutions for Digital Piracy

Eliminating piracy in the foreseeable future is a next to impossible task. There will always be people seeking ways to circumvent laws for a variety of reasons. There is hope, however. Even though wiping out piracy is not feasible, reducing this theft of digital material can be accomplished.There are four possible approaches--raising awareness, improving business strategies, adjusting enforcement techniques, and embracing policy amendments--are outlined here.

Raising Awareness

- Getting the message across to the new generations of Digital Natives

It is human nature to want to fit in with the rest of the populace. For example, if the majority of Trevorâs peers does not condone or commit piracy, it is highly unlikely Trevor will spend Friday nights at home downloading the latest blockbuster for he will be at the movie theatre watching the film with his friends. Thus, it is necessary to embed piracyâs immoral ideologies as early as possible in the heads of rising digital natives.

Although the representatives of the entertainment industry are currently pushing massive anti-piracy educational campaigns onto the public sphere, their efforts are not enough. The facts about piracy need to be incorporated into public school curriculums across the country. High school government classes should stress the consequences of copyright infringement. Parents should take part in addressing the dangers of piracy before they teach their children how to use computers. With a solid piracy awareness educational program in place, next generations of internet users will be ready to make rational and informed decisions about electronic theft.

- Programs in place for kids in secondary schools

- Programs in place for college students

- Other information sources

- Opposing viewpoints

Improve Business Strategies

Steps the software, entertainment, and gaming industries can take to adapt to the stubborn mindsets of digital natives.

- Adapting to the new digital environment

- Embrace the inevitable online music movement

- Develop better technologies to aid sales

- Providing legal, more attractive alternatives

- Reduce material costs of current physical albums

- Renew incentives to collect

The main incentive to obtain pirated files instead of purchasing them from a legitimate seller is because of the undesirable high prices of genuine media. In a study conducted by the RIAA, the consumer prices of producing a CD nearly rose 60% between the years of 1983 and 1996. Fortunately, the price of blank CDs fell 40% during this period, otherwise âaverage retail price of a CD in 1996 would have been $33.86 instead of $12.75â [1]. The RIAA notes because âthe amount of music provided on a typical CD has increased substantially, along with higher quality in terms of fidelity, durability, ease of use, and range of choices,â not to mention todayâs insanely over the top marketing strategies, the prices of production has been consistently on the rise.

This price trend also is occurring in the DVD sales industry. With the DVD player penetration rate in American households up from 23.6% in 2001 to 76.2% in 2005, DVDs are definitely on demand [2]. The average price of a DVD title, however, rose from $20.52 to $21.35 from 2001 to 2005 while the price of blank DVDs were falling lower and lower [3]. Consumers who are always hunting for deals turn to free P2P services or cheaper pirated versions of media because the real stuff is simply too expensive.

- Good examples

- Apple iTunes Music Store

- The New Naspter

- BitTorrent and MPAA Join Forces [4]

Adjust Enforcement Techniques

Parts of this section were adapted from Chen Fang's freshmen seminar paper.

The RIAA announced in July 2003 its intent to start gathering evidence in order to sue end users for illegally downloading copyrighted content via file sharing networks. Several months later, the big day finally came. On September 8th, 2003, the RIAA issued the first 261 lawsuits in what was to become an onslaught of charges. By May of 2006, newspapers have reported "the RIAA had sued more than 182,000 individuals for illegal downloading of music." [5] Although there were several cases that were fought extensively by the defendants, on average, each suit was settled for around $3000. The Motion Pictures Association of America, an organization that serves "as the voice and advocate of the American motion picture, home video and television industries," was not far behind in its user litigation endeavor. [6] Around one year after the RIAA's announcement, the newly appointed CEO of MPAA, Dan Glickman, declared at a UCLA press conference that "the studios will begin suing online movie swappers in the next few weeks." [7] Commenting on the recording industry's pursuit of piracy, Glickman told USA Today - "we wanted to watch their progress first and have some time to evaluate options. In the short term, it caused them some problems, but long term they were helped greatly by the campaign."

Problems? Since the day the RIAA initiated its first wave of copyright infringement suits, there have been many complaints voiced by analysts over the practice of suing loyal consumers. Wharton legal studies professor Richard Shell proclaimed that the RIAA "has gone one step too far with its latest legal move. Industries have a completely different strategic relationship with customers than they do with rivals. And this sort of strategy does not play well in the court of public opinion." The questionable effectiveness of this controversial business strategy was hyped to an even higher level when some targets of the RIAA became simply ridiculous. Curious media networks, always hungry for another eye catching story, had a field day when people like Sarah Ward received her lawsuit in the mail. For some odd reason, Ward, a grandmother residing in Massachusetts was charged for downloading "hard-core rap music." [8] It turns out this wasn't the only obscure case, given that little girls and old grandpas were also part of the pool of 261 unlucky individuals hit by RIAA's first round of lawsuits. "Brianna Lahara, a twelve-year-old girl living with her single mother in public housing in New York City" and "Durwood Pickle, a 71-year-old grandfather in Texas" were both charged for downloading copyrighted content through illegal file sharing networks. [9] The profiling of stereotypically awkward individuals did not stop here. In the years following the first lawsuits, the RIAA had inspired many sardonic headlines - "RIAA drops case against mom; sues her kids", "RIAA Sues Deceased Grandmother," and "RIAA Sues Yet Another Person Without A Computer" just to list several examples. Though some of these cases did turn out to be mistakes, the majority of them actually were legitimate accusations. Nevertheless, the large majority of the populace on popular forums, blog sites, and the news media concur with Professor Shell's belief. In their opinion, chastising, ridiculing, and sometimes flat out mocking the RIAA's foolish actions made sense.

- Setting the examples (for the prosecution)

Setting Examples

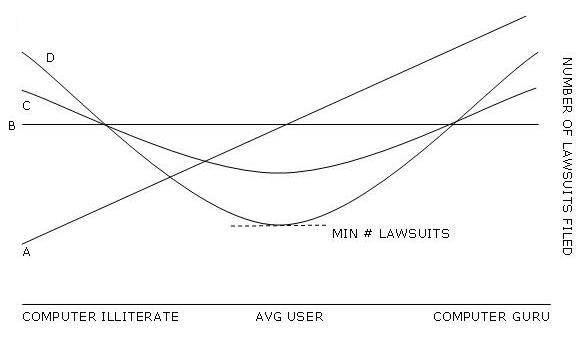

A moderate level of user litigation theoretically is beneficial to the recording industry. However, the question of who should be sued is still left to be determined. Is it right to sue grandpas, grandmas, and little kids? Is it fair for the recording industry to issue the same settlement amount to a computer amateur who shared several media files and a computer guru who finally got caught? Contrary to popular belief, litigation of "innocent" little kids is in fact the right thing to do. Logically, this might not make sense, but if observed from a grander economic perspective, prosecuting downloaders who are sympathetic to the recording industries is the right way to go.

Currently, the RIAA has been known to mainly target uploaders or "individuals who were allowing others to copy music files from their shared folders." [12] The piracy awareness materials published by the MPAA have also suggested the movie industry is following somewhat the same policy. In a short video clip documenting what MPAA calls "the Piracy Avalanche," the narrator concludes with the following sentence: "By eliminating topsites, the Motion Picture Association is targeting Internet piracy at its source and putting a lock on the trigger of illegal downloading and distribution of copyrighted material worldwide." [13] "Topsites" according to the MPAA are centralized distribution centers where the chain of piracy starts. In their opinion, if these initial outlets of pirated material are taken down, then online movie piracy would be reduced a great extent. Although this hypothesis may be true, the execution of the plan is too far-fetched. The effort needed by the MPAA to terminate a topsite is far greater than the effort needed by a single computer-adept person to launch services in another location. Only with the full cooperation of governments around the world, will this proposal be successful.

In addition to the implausibility of targeting piracy at its deepest roots, the idea of suing domestic high uploaders also does not make sense. The RIAA claims that piracy "costs the music industry more than 300 million dollars a year domestically." [14] Although no one knows how this number is estimated, one fact needs to be clarified. From an economics point of view, the recording industry is only losing money when a user who originally intended to buy legal media forgoes this process to download illegally. A computer guru who never spent a single dime on the recording industry in his or her life technically does not count in this losses figure. Therefore, it is unwise for the MPAA and the RIAA to simply concentrate on people who upload a lot. To these individuals, getting a cease and desist notice from their ISP will not affect ideologies already imbued in their heads. On the other hand, if a computer novice who used to buy CDs and DVDs legitimately got the same warning, this wakeup call would much more likely turn them back into buying media the old fashioned way.

Line A shows a generalization of MPAA and RIAAâs current business practices. Assuming that computer gurus upload a lot more than a computer notice who is trying Kazaa for the first time, the number of lawsuits filed increases as computer experience increases. Instead of only concentrating on bringing down the uploaders, the recording industry should increase the number of lawsuits aimed at the first time user. If there was a way to use bots scanning P2P networks to keep track of the reoccurrence of IP addresses, at the optimum situation (line D), the number of lawsuits should be directed to both computer illiterate sympathizers who are using the P2P network for the first time and old school uploaders who are fueling the illegal material. With this two prong attack, the recording industry will not only curtail the spread of piracy but also instill fear using illegal mediums to acquire media in the community of customers. "How well law regulates, or how efficiently, is a different question. But whether better or not, law continues to threaten a certain consequence if it is defined." [15] The RIAA and MPAA should continue to use the powers of law to deter piracy.

Employing New Technologies

- Using technologies to their advantage

- Preventing Movie Piracy (Camcording) [16]

- DRM

Using the Masses

Covenant i-Fan Model

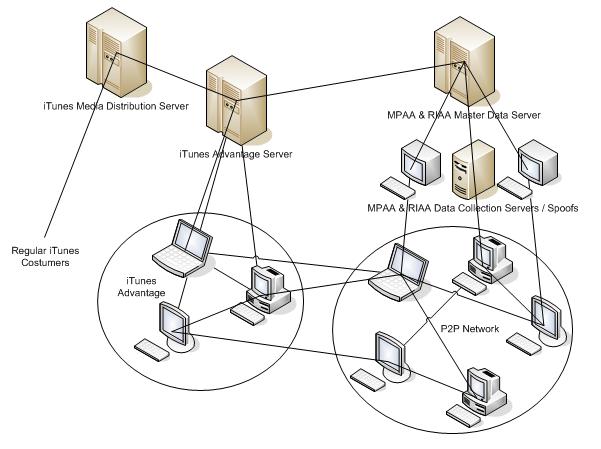

Although the architecture of the internet allows for programmers to construct P2P infrastructures, the same architecture can also be used to control or at least disrupt these networks. The most common countermeasure the RIAA and the MPAA have used is hiring third party security companies such as Covenant Corporation to upload false media files to discourage users from downloading. Covenant Corporation uses its own servers to mimic users on P2P networks, uploading unusable copyrighted files to unsuspecting downloaders. Through this i-Fan system, Covenant Corporation also encourages users to distribute these files through their personal computers.

Covenant took a step in the right direction but failed to produce the necessary results because of the poor user base. i-Fan offers its users "free money" to help intentionally disseminate these spoof files, however, does not guarantee everyone assisting this project rewards. Over the course of the past three years, only six winners have been announced. [17] So where can the MPAA and RIAA harness a big enough user base to start the anti-piracy movement? iTunes. As of 2006, Wired magazine reported that iTunes has over 200 million active customers. [18] If the MPAA and RIAA can convince Apple to tack on something like i-Fan into its iTunes program, the recording industry will have a lawful and practical method of bringing down P2P networks.

The figure above provides a visual representation of what "iTunes Advantage" adds on to the existing infrastructure. The larger circle on the bottom right hand corner is the existing P2P network. Today, the only spoof computers that upload senseless material into the P2P network are the ones hired by the MPAA and RIAA. With iTunes Advantage, every user currently in the iTunes community has the option of helping to stop piracy. If this plug-in is turned on, iTunes will use built in P2P protocol to upload corrupted content to select P2P networks. To make the deal even more attractive, the recording industries might provide certain amount of iTunes store credit for every megabyte uploaded. With cooperation from Apple, the recording industry can modify the architecture of the internet to stop piracy.

Hong Kong Youth Ambassador Model

If you can't beat them, recruit them. Instead of hiring professional corporations to implement sophisticated anti-piracy mechanisms and paying an army of lawyers to prosecute the few who are caught, the Hong Kong government launched a revolutionary new anti-piracy program consisting of today's most talented, internet-adept populace -- our kids. Starting on July 18th, 2007, "the Hong Kong government plans to have 200,000 youths search discussion sites for illegal copies of copyrighted songs and movies and report them to the authorities. The campaign has delighted the entertainment industry but prompted misgivings among some civil liberties advocates." [19] The Youth Ambassadors program consist individuals as young as 9 to scour the internet for links to illegally uploaded copyrighted content. Governmental officials announced, "all members of the Boy Scouts, Girl Guides and nine other uniformed youth groups here, will be expected to participate." "We are not trying to manipulate youths and get them into the spy profession," Tam said. "What we are just trying to do is arouse a civic conscience to report crimes to the authorities." [20]

Youth Ambassador program has three main goals. One, the program is aimed to promote the importance of intellectual property rights. "Educating youths to respect copyrights is a central goal of the program, officials said. "A lot of Internet piracy is done by young people, particularly in their teens, and the difficulty is it's almost becoming a fashion to download music, download video," said Joseph Wong, the Hong Kong secretary of commerce, industry and technology." Two, by hiring today's youth, government officials hope to expand its abilities to monitor illegal internet activity. And three, if enough reports come in, the government hopes to reduce the amount of illegal BitTorrent seeds available online. [21] This project "was one of the main campaigns in a series of publicity and educational programs for IPRs protection launched by Commerce, Industry and Technology Bureau on May 29" of this year. In this original pilot run, 60% of all postings to illegal content on forums have been removed. [22] Hong Kong is setting an anti-piracy methodology for the rest of the world to follow.

Embrace Policy Amendments

One of the main motivations behind piracy resides in the desire to bypass barriers to obtain rare or restricted commodities. Whether for professional, creative, or leisure use, people are in constant search for new pictures, music, movies, games and other digital fads. Recently in the United States, thanks to stronger copyright laws, it has become harder and harder to legally acquire these works without going through the hassle of obtaining the correct licenses. Although the ideas patented by private industries were never available for free, public consumption, the Copyright Law revision of 1976 changed the default copyright standards for creative works. Before this fateful year, when an author created a new work of art, it was not automatically protected by copyright unless the author officially applied through the proper government channels. After these legislative changes, "creative works are now automatically copyrighted." [23] Now copyright was applied by default, for "once someone has an idea and produces it in tangible form, the creator is the copyright holder and has the authority to enforce his exclusivity to it." [24] These alterations to the law restrict the number of works available in the public domain, increasing the incentives to commit piracy.

Free & Copyleft-Like Licensing

Long before the popularization of personal computers, the internet and the onset of digital piracy, programmers and users alike have supported alternatives to copyright. Although forcing all goods and services in a society be offered for gratis is an extreme solution to the piracy, the action will not only stifle innovation but also crumble a society's economy, thus its infrastructure to exist. Instead, the present copyright laws can be adjusted to better accommodate the creative needs of future generations. Copyleft is a copyright license spin off that allows for the modification of would be copyrighted content. Copyleft "removes restrictions on distributing copies and modified versions of a work for others and requiring that the same freedoms be preserved in modified versions." [25] Currently there are several notable movements that have been offering such substitute licensing options: Free Software Foundation's GNU GPL, Open Source Initiative's Academic Free License, Creative Commons License, and quite a few less popular licenses like MIT, BSD, Uol/NCSA, and Apache.

Free Software Foundation & GNU GPL

In 1985, Richard Stallman founded a non-profit organization called The Free Software Foundation. It is "dedicated to promoting computer users' rights to use, study, copy, modify, and redistribute computer programs." [26] Since its establishment, the FSF widely known for its free software advocacy. Besides publishing a very popular GNU GPL (GNU Lesser General Public License), FSF also released one of the first open source operating systems called GNU (GNU's Not Unix). Today, GPL is used by numerous software programmers and corporations as the official license for their software. Popular Wikimedia foundation's wiki projects are all released under the GNU Free Documentation License.

Open Source Initiative's & APL

After a decade free software policy promotion, the FSF's goals became distorted by the large amounts of actual "zero cost" software running under its GNU license. This made FSF look like an anti-commercial, anti-market organization rather than a outlet of free expression and free speech. Around 1998, a sect of the free culture movement followers gathered together to push for a less ambigous goal. These people "advocated that the term free software be replaced by open source software (OSS) as an expression which is more comfortable for the corporate world." [27] Founded by Eric Raymond and Bruce Perens in February 1988, the OSI (Open Source Initiative) "sought to bring a higher profile to the practical benefits of freely available source code, and they wanted to bring major software businesses and other high-tech industries into open source." [28] Raymond suggested the development of open source software should following his "Bazaar" model, which included the following traits: users treated as co-developers, early releases, frequent integration, several versions, high modularization, and dynamic decision making structure. Popular projects like Apache, Linux, Netscape, and Perl follow this model. Right now the Open Source Initiative serves as a "community-recognized body for reviewing and approving licenses as OSD (open source development) conformant." [29]

Creative Commons & CC License

Creative Commons is a non-profit organization that allows for âauthors, scientists, artists, and educators easily mark their creative work with the freedoms they want it to carry.â [30] Founded by Lawrence Lessig in 2001, Creative Commons offers free licensing to the whole spectrum of individuals from every corner of the media background. These Creative Commons licenses come in several different flavors, offering selective protections such as forbidden commercial use or mandatory sharealike distribution. They enable âcopyright holders to grant some or all of their rights to the public while retaining others through a variety of licensing and contract schemes including dedication to the public domain or open content licensing terms. The intention is to avoid the problems current copyright laws create for the sharing of information.â [31] By using CC Licenses, producers of what would be considered protected intellectual property can release their works to the public in confidence, for consumers will know exactly what they can and cannot do with the licensed work.

Unlike the GNUâs GPL, which is mainly used by programmers to license software creations, Creative Commons licenses can be applied to all kinds of media. CreativesCommons.org provides custom-made online tools and straightforward directions to help users license their work. Once a proper license is chosen, the online community has access to three editions â one laymenâs terms for regular users, one in legal writing for lawyers, and one in code for computers. Comprehensive translations are also available for international users.