Digital Piracy: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| (11 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

[[Portal:Digital Piracy]] | |||

= Narratives = | = Narratives = | ||

| Line 524: | Line 525: | ||

[[Image:Free software foundation logo.jpg|thumb|369px|left|Free Software Foundation Logo]] | [[Image:Free software foundation logo.jpg|thumb|369px|left|Free Software Foundation Logo]] | ||

In 1985, Richard Stallman founded a non-profit organization called The Free Software Foundation. It is "dedicated to promoting computer users' rights to use, study, copy, modify, and redistribute computer programs." [http://www.fsf.org/] Since its establishment, the FSF widely known for its free software advocacy. Besides publishing a very popular GNU GPL (GNU Lesser General Public License), FSF also released one of the first open source operating systems called GNU (GNU's Not Unix). Today, GPL is used by numerous software programmers and corporations as the official license for their software. Popular Wikimedia foundation's wiki projects are all released under the GNU Free Documentation License. | |||

"dedicated to promoting computer users' rights to use, study, copy, modify, and redistribute computer programs." [http://www.fsf.org/] Since its establishment, the FSF widely known for its free software advocacy. Besides publishing a very popular GNU GPL (GNU Lesser General Public License), FSF also released one of the first open source operating systems called GNU (GNU's Not Unix). Today, GPL is used by numerous software programmers and corporations as the official license for their software. Popular Wikimedia foundation's wiki projects are all released under the GNU Free Documentation License. | |||

'''Open Source Initiative's & APL''' | '''Open Source Initiative's & APL''' | ||

| Line 531: | Line 531: | ||

[[Image:Open source logo.jpg|thumb|154px|right|Open Source Logo]] | [[Image:Open source logo.jpg|thumb|154px|right|Open Source Logo]] | ||

After a decade free software policy promotion, the FSF's goals became distorted by the large amounts of actual "zero cost" software running under its GNU license. This made FSF look like an anti-commercial, anti-market organization rather than a outlet of free expression and free speech. Around 1998, a sect of the free culture movement followers gathered together to push for a less ambigous goal. These people "advocated that the term free software be replaced by open source software (OSS) as an expression which is more comfortable for the corporate world." [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Open-source_software] Founded by Eric Raymond and Bruce Perens in February 1988, the OSI (Open Source Initiative) "sought to bring a higher profile to the practical benefits of freely available source code, and they wanted to bring major software businesses and other high-tech industries into open source." [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Open-source_software] Raymond suggested the development of open source software should following his "Bazaar" model, which included the following traits: users treated as co-developers, early releases, frequent integration, several versions, high modularization, and dynamic decision making structure. Popular projects like Apache, Linux, Netscape, and Perl follow this model. Right now the Open Source Initiative serves as a "community-recognized body for reviewing and approving licenses as OSD (open source development) conformant." [http://www.opensource.org/about] | |||

'''Creative Commons & CC License ''' | '''Creative Commons & CC License ''' | ||

[[Image:Creative commons logo.jpg|thumb|200px|left|Creative Commons Logo]] | [[Image:Creative commons logo.jpg|thumb|200px|left|Creative Commons Logo]] | ||

Creative Commons is a non-profit organization that allows for âauthors, scientists, artists, and educators easily mark their creative work with the freedoms they want it to carry.â [http://www.creativecommons.org/] Founded by Lawrence Lessig in 2001, Creative Commons offers free licensing to the whole spectrum of individuals from every corner of the media background. These Creative Commons licenses come in several different flavors, offering selective protections such as forbidden commercial use or mandatory sharealike distribution. They enable âcopyright holders to grant some or all of their rights to the public while retaining others through a variety of licensing and contract schemes including dedication to the public domain or open content licensing terms. The intention is to avoid the problems current copyright laws create for the sharing of information.â [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Creative_Commons] By using CC Licenses, producers of what would be considered protected intellectual property can release their works to the public in confidence, for consumers will know exactly what they can and cannot do with the licensed work. | |||

Creative Commons | |||

[http:// | |||

[http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ | |||

Unlike the GNUâs GPL, which is mainly used by programmers to license software creations, Creative Commons licenses can be applied to all kinds of media. CreativesCommons.org provides custom-made online tools and straightforward directions to help users license their work. Once a proper license is chosen, the online community has access to three editions â one laymenâs terms for regular users, one in legal writing for lawyers, and one in code for computers. Comprehensive translations are also available for international users. | |||

= Reflections = | = Reflections = | ||

| Line 820: | Line 807: | ||

[http://arstechnica.com/news.ars/post/20070723-bill-would-force-top-25-piracy-schools-to-adopt-anti-p2p-technology.html Bill would force "top 25 piracy schools" to adopt anti-P2P technology, 2007] | [http://arstechnica.com/news.ars/post/20070723-bill-would-force-top-25-piracy-schools-to-adopt-anti-p2p-technology.html Bill would force "top 25 piracy schools" to adopt anti-P2P technology, 2007] | ||

== RIAA Pre- | [http://news.bbc.co.uk/go/pr/fr/-/2/hi/entertainment/6993752.stm BBC News - Pop Star Prince gets togh on Web Pirates, 09.13.07] | ||

== RIAA Pre-Litigation Letters == | |||

[http://riaa.com/newsitem.php?id=780E8751-0E03-4258-D651-F991B66E1708 July 18, 2007: Sixth Wave] | [http://riaa.com/newsitem.php?id=780E8751-0E03-4258-D651-F991B66E1708 July 18, 2007: Sixth Wave] | ||

Latest revision as of 20:29, 24 November 2007

Narratives

- Trevor is doing a project for school. Since he is very adept at video mashups, he decides to use clips from different TV shows and movies to assist him with the project. After completing the masterpiece, Trevor is very excited about his work and wants not only his class but also the whole world to see his creation. Due to the fact that long segments of copyrighted material were used in the making of this clip, he decides to post the video onto YouTube with an obscure name to avoid detection and uploads it onto five other video sharing services DailyMotion, Revver, GoFish, MySpace Video, and Facebook Video to act as mirrors. He then embeds the clip onto his blog and uses IM, email, text messaging, and Twitter to spread the word about this update.

Involves the use of the following applications: Adobe Premiere, Audacity, Trillian, Thunderbird

And services: YouTube, Daily Motion, Revver, GoFish, MySpace, Facebook, Textem, and Twitter.

- Questions raised from this scenario:

- What constitutes fair use?

- Do copyright laws impede creativity?

- Trevor and friends are hanging out in his basement on a lazy Sunday afternoon. They just watched a trailer of an upcoming blockbuster film and the whole group is very excited -- they canât wait to get in line to see the first midnight showing. Unfortunately, the filmâs release date is one week away. With nothing else to do, Trevor proposes that he could obtain a copy of the film via a private torrent network whose administrator is a member of an infamous release group. A few of his friends brings up the concern about piracy, but since the group is at Trevorâs house, using Trevor's internet connection, nobody objects -- in fact, a few never realized this was possible. After a quick debate about what to do, soon the majority of the group wants the movie downloaded and burned to discs for everyone to have.

Involves the use of the following applications: Quicktime, uTorrent, PeerGuardian 2, DivX Player, XviD Video Codec, AC3 Audio Codec

And services: <Torrent Website>, <Release Group>

- Questions raised from this scenario:

- Who should be more responsible for the piracy? The release group or the end user?

- How does group mentality play affect piracy?

- After seeing Trevor successfully obtain the movie, one of Trevorâs friends decide to get more movies from a P2P program he installed a while back. After firing the application up, his computer freezes. Not knowing what happened, Trevorâs friend does a simple force reboot and after the restart, everything seems fine. In the background processes, however, the P2P program automatically shared his whole media folder to the rest of the P2P community without telling the user.

Involves the use of the following applications: <P2P Application>

- Questions raised from this scenario:

- If a P2P program automatically shares all the media on a user's computer and the user is accused of copyright infringement, who should take the blame? The P2P company or the end user?

- The tech companies hired by the media industries to track down internet pirates is known for only targeting uploaders, rarely downloaders. Is this technique working?

- Trevor's family live in a fairly large condominium complex. Although all the computers in Trevor's house are connected via an encrypted wireless local area connection, Trevor's laptop has the ability to detect and connect to several other neighbor's wireless routers from the comforts of his bedroom. Since his laptop's wireless card is set connect to the closest router, Trevor often surfs the net & downloads copyrighted media using his neighbor's connection.

Involves the use of the following applications: <Wireless Configuration Utility>

- Questions raised from this scenario:

- A large majority of home wireless routers do not ship with WEP and WPA security turned on, causing many personal networks to be exposed to outside threats. If an outsider uses your wireless connection to facilitate illegal file sharing, what rights do you have as the innocently accused?

Introduction to Piracy

In the simplest terms, piracy is obtaining materials without the proper rights of legal ownership. In a broader sense, piracy can represent a whole range of intellectual and physical robbery. Like what the traditional usage of this term suggests, the theft committed by ruthless sea barbarians in the early 1700s is analogous to the present day methods to wrongfully acquire or distribute copyrighted material. Yes, the recent surge in pirated Pirates of the Caribbean films is, least to say, ironic.

The main driving force behind the argument against piracy centers on the degree of copyright infringement. The creator of a new piece of work has exclusive rights or ownership over all individual products of labor. Exclusive rights include, but are not limited to, distribution, reproduction, the ability to perform and make derivatives of the original. Under United States and most foreign law, copyright infringement is the unauthorized use of any works or materials secured by copyright. Piracy impinges on the copyright ownerâs exclusive rights without a license to do so and thus is considered a form of copyright infringement.

Why are copyrights necessary? Copyrights and the consequences of copyright infringement not only help protect intellectual property and ownership but also benefit society as a whole. By prohibiting duplication of new products and ideas for a designated period of time after creation, these laws prevent third party profiteers from stealing intellectual property and making a living from the hard work of others. Copyrights provide sufficient incentives for individuals to embark on revolutionary research, make their discoveries, and present their own creations without having to worry about ownership issues. These laws promote society's scientific and intellectual progress while piracy works as the counterforce.

Currently, the piracy problem spans many corporate sectors. The MPAA, RIAA, ESA, and SIAA, representing the movie, music, gaming, and software industries respectively, have all taken drastic measures to cope with the repercussions from illegal sharing of their clientsâ copyrighted works. Besides publishing annual damage reports that rave about the millions upon billions of lost profit and issuing pre-litigation notices to known violators, industries have begun collaborating with educational companies to bring piracy awareness into schools.

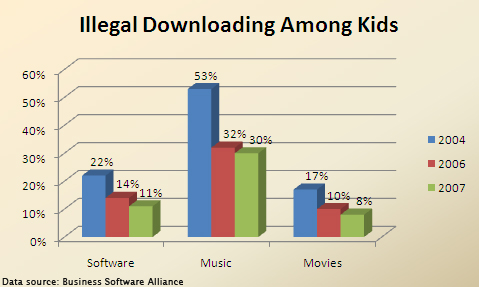

Although some critics of these so-called âprofit seekingâ businesses frown upon the use of educational programs designed by paid business partners, the piracy-ridden industries are targeting the right demographics. [1] [2] As studies conducted by third party researchers show, up and coming generations of digital natives are more prone than any other age group to experiment with and actually commit piracy. In a 2006 study, L.E.K. consulting group found the typical internet pirate is a male between the ages of 16 and 24. They reported, â44 percent of MPA company losses in the U.S. are attributable to college students.â [3] Growing up in an environment immersed with different technological facets, digital natives confront the copyright issue much earlier in childhood. More and more of our youth are desensitized about piracy and intellectual property rights at younger ages. In a recent PEW study, researchers found that around half of the young students interviewed were not concerned with downloading and sharing of copyrighted content for gratis. Teens who download music online agree, âitâs unrealistic to expect people to self-regulate and avoid free downloading and file-sharing altogether.â [4]

Overview

Technological advancements in years saddling the new millennium brought sweeping changes to the way data is transferred across the world. The rapid increase in the availability and acceptance of broadband internet connections has allowed people from the far reaches of the globe to download large multimedia files at much faster speeds than ever before. Sharing files between computers became easier for the general population to understand. The once dominant UseNets and IRC channels slowly gave way to user-friendly graphical user interface (GUI) peer-to-peer (P2P) programs where anyone can make a simple search to produce desirable results. Emerging technologies such as Wikis and BitTorrent coupled with old tools like email and instant messaging provided additional techniques where information can be transferred from one client to the next. Finally, the adoption of standardized media formats improved the sharing experience as a whole. All of these changes, old and new, provided the foundations for the present day's pervasive illegal distribution of copyrighted material.

Classifications

Since the piracy problem is pertinent across many fields, the definition of this term and possible classifications have been extremely controversial over the years. While members of the justice system used piracy and theft almost interchangeably, people on the other side of the aisle view this practice as a grand exaggeration of reality. To them, it is unfair to compare downloading a song with real life thievery, or in this case, the carnage of 17th century sea "pirates." Even the organizations representing the large media and software industries do not have standard, unified definition for what they are fighting. MPAA defines piracy as "a serious federal offense." As for the different kinds of piracy, MPAA only mentions "internet piracy of movies, DVD copying, illegal sales and theatrical camcording." To the ISAA, "making additional copies, or loading the software onto more than one machine, may violate copyright law and be considered piracy." RIAA defines piracy as "the illegal duplication and distribution of sound recordings." Each organization is representing its respective industry, only showing pertinent consumers mere pieces of the puzzle. A definitive, yet agreeable definition for piracy and an universal way to classify the many faces of this issue are needed.

Piracy can be classified into two categories - digital and physical. Digital piracy is the illegal duplication and distribution of copyrighted content via electronic means. While the usage of online (peer-to-peer) P2P networks is the most pervasive outlet of digital piracy, hosting copyrighted files such as MP3s, movies, and software on web servers, uploading copyrighted media on video sharing sites, and even simpler ways of distribution such as via email or instant messaging are also considered illegal digital piracy. Similar to digital piracy, physical piracy involves the illegal duplication and distribution of works, but in physical form. Digital media can be illegally burned onto mediums such as CDs, DVDs and sold for a fraction of the retail price. Books, newspapers, magazines, course packs, journals, research and reports can also be duplicated in physical form and distributed. In fact, the MPAA reports, for 2005 "62 percent of the $6.1 billion loss result from piracy of hard goods such as DVDs, 38 percent from internet piracy." [5] Physical piracy of media and other forms of content are much more pervasive on a global scale. This method of copyright infringement can be further classified into individual license, corporate to end-user, reseller and distributor violations.

Categorizing piracy by methodology only answers the "how" question. "Why" people pirate can be grouped by a measurement of intentionality. Kids and adults alike have different reasons for why they choose to download from P2P networks or buy counterfeit media. Some, however, are quite unaware of their actions while others are completely oblivious between what is right and wrong. In a recent ZDNet report on UK businesses running Windows, "Microsoft would not put a figure on how much it loses from unintentional piracy, but said that while 85 percent of UK small businesses run Microsoft software, only 15 percent pay for it." [6] All of this, of course, hinges on intentionality. Individuals who are completely aware of their actions are considered director facilitators of digital or physical piracy. From the acquirers of prerelease content, to the online intermediaries, from the distributors to the customers, this group includes people anywhere on the piracy chain. Intentional piracy usually involves some sort of monetary gain at the loss of the copyright holder. Individuals somewhat aware of piracy are usually consumers of counterfeit content. They understand to an extent what they are doing is wrong but choose to go ahead with it for various reasons such as personal enjoyment or curiosity. Educating these indirect facilitators the wrongs of piracy is the recording industries' best chance at curbing this problem. Finally, consumers completely unaware of piracy are usually those who are victims of counterfeit scammers or those whose computer or personal network has been hijacked to illegally contribute copyrighted material.

Origins

In the last millennium, there were only a few landmark innovations affecting the dissemination of media content. Gutenbergâs invention of the printing press in 1450 allowed for easy and inexpensive duplication of paper works. With the assistance of moveable type, productivity of scribes (now hired machine workers) increased exponentially. As profit margins shot through the roof, the publishing industry was born. In the late 1970s, early 1980s, the introduction of the Sony Walkman gave humans the capability to record audio while the videocassette system did the same for video. In the 1990s, the popularization of CD/DVD optical disk technology gave birth to the new era of digital recording. The 21st century ushered in the acceptance of new digital mediums. Combined with the enormous success of the internet, computers and newly developed network protocols took information sharing to a new level. Each one of these new "machines" included a "mechanism" for which a certain "media" was affected. Each innovation established or revolutionized an industry. Each provided a faster, even better way to spread information. Each, however, brought with it intellectual property issues, for each forced or is forcing policy makers to amend copyright standards.

| Media | Mechanism | Machine |

|---|---|---|

| Paper | Movable Type Publishing | Printing Press |

| Cassette/VHS Tape | Magnetic Recording | Walkman/VHS Machine |

| CD/DVD | Optical Disk Recording | CD/DVD Recorder |

| Standardized Computer Files | P2P/Torrent Networks | Personal Computer |

On June 1st, 1999, Shawn Fanning, a student from Northeastern University, released what would be called "the godfather of peer to peer programs" â Napster. At that time, although there were other technologies facilitating the sharing of media, "Napster specialized exclusively in music ... and presented a user-friendly interface." [7] Soon after being launched, this easy to use, cost-free program became wildly popular because everyday computer users had enough basic technical knowledge to contribute to the file sharing movement. Napster's sensation, however, was short lived. Its "facilitation of transferring copyrighted material raised the ire of the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA), which almost immediately â in December 1999 â filed a lawsuit against the popular service." [8] Because Fanning earned profits through advertisements and operated the project via a client-server protocol with a centralized file list, the RIAA push for intentional copyright infringement ultimately succeeded.

Napster's immense success planted the seed for today's P2P debacle. On one hand, this innovation sparked the countermovement by the RIAA and other recording companies to curtail infringement. On the other hand, Fanning's concept of dedicated media distribution GUI programs inspired next generations of P2P coders to create iterations of the Napster design even more insusceptible to the current copyright laws. The 1986 "Betamax case" allowed Sony to manufacture VCRs "because the devices were sold for legitimate purposes and had substantial non-infringing uses" (Betamax). In the cases brought up against these new P2P projects, even though the prosecution was successful in proving the Betamax argument invalid, the victory in the courtroom only fueled the rapid spawning of new P2P projects.

In March 2001, the FastTrack protocol allowed for a more distributed network without a centralized sever. Faster computers in the network now has the ability to become supernodes, or machines with server-like capabilities to help out slower clients. Newer P2P programs like KaZaa, Grokster, and iMesh successfully implemented this protocol and gained millions of users. Two years later, "FastTrack was the most popular file sharing network, being mainly used for the exchange of music mp3 files. Popular features of FastTrack are the ability to resume interrupted downloads and to simultaneously download segments of one file from multiple peers." [9] During the same decade, true distributed network protocols such as the open source Gnutella and eDonkey 2000 also caught on with mainstream P2P file sharers. Likewise spawning other P2P clients, Limewire, Morpheus, and eDonkey. Compared to Napster, these newer networks were able to attain higher maximum speeds because every client also had the capability to share files. Also, since the copyrighted material were stored on individual computers, with the proper disclaimers, the P2P client companies were able to brush off the majority of legal accusations.

The acceptance of the mp3 format in the mid 1990s allowed users to compress songs into several megabyte files, all of which were easily distributable throughout the digital world. In the early 2000s, DivX, a newly developed video compression codec did the same for video. As more households switched over to broadband internet, the ability to transfer large files finally became plausible. However, even with DivXâs help, typical compressed DVD rips still hovered above 600 MB. Since traditional P2P protocols could not handle the new bandwidth demand efficiently, a newer distributive protocol called BitTorrent was quickly adopted.

BitTorrent was developed by Bram Cohen in 2001. By splitting large files into sizable pieces, data can be widely distributed and shared "without the original distributor incurring the entire costs of hardware, hosting and bandwidth resources." [10] For a client to download additional data, one must supply requested chunks of the larger file to newer recipients. Cohen's implementation not only proved to be incredibly efficient, but also managed to exploit a legal loophole. While the initial releases of the BitTorrent system depended on trackers to operate, these servers answered the requests clients only by giving them the location of other computers who are concurrently sharing the same sought after file. Since tracker servers did not host any of the copyrighted content, the prosecution had a harder time shutting down these organizations. BitTorrent soon grew to become the sharing mechanism of choice.

Digital piracy only constitutes a portion of the whole picture. True, today's extensive counterfeit CD/DVD markets are largely fueled by the established presence of piracy in the digital realm. Resellers and distributors usually get the content to copy from online sources. But, the history of physical piracy can be traced back to the days of floppy disks and cassette tapes. In 1964, the Philips company brought compact audio cassette technology to the United States. Although there were other magnetic cartridge technologies available, Philip's decision to license the format for free made compact cassettes the most accepted recording medium during this time. [11] In the 1970s and 1980s, cheaper multi-track recording mechanisms for artists and the consumer compact cassette boom prolonged the popularity of this new medium. The trading of these recordable cassettes among music fans across the U.S. and U.K. via the mail was dubbed "cassette culture." [12] Acceptance of floppy disk technology starting from the early 1980s provided users an easy way to copy computer related files. Copyrighted computer software and games especially could be easily duplicated using these disks. Of course, anti-piracy campaigns also started as a reaction to these new fads. The British Phonographic Industry, a music trade group in the 1980s, launched an anti-piracy campaign with the slogan "Home Taping Is Killing Music." Similar to the RIAA's concerns today, the BPI was afraid that the rise of a new recording medium (in their case, the cassette tapes) would hurt legitimate record sales. In 1992, the Software Publishers Association produced an anti-piracy campaign centered around a video commercial called "Don't Copy That Floppy." [13]

Current Methodologies

Advent of the internet and the rapid increase of personal computers means more people than ever before have the capability to share information online. Though these advancements give users unprecedented access to the world's data, enforcing proper copyright restrictions while allowing justifiable sharing freedoms have not been attained. Thus, many have pointed to these new technologies as the facilitators of so-called "digital piracy." Today, users employ many different applications and services to illegally transfer copyrighted material. Factoring intentionality out of the equation, this section aims to introduce these online trade tools.

Local sources

Highlights: Live Messenger, E-mail, YouSendIt, MyTunes

The easiest and often times fastest way a person obtains copyrighted materials is from local, direct sources. Friends, family members, classmates -- an individual's immediate relations are commonly the people one asks when in need of a song, copy of a TV show, or a recent movie. Popular chat software like Microsoft's Live Messenger, AOL's IM, even Yahoo Messenger all support some form of a file transferring mechanism allowing these exchanges to happen. A few clicks and a potentially copyrighted file is on its way. Thanks to the recent milestones in the email industry, ever increasing account quotas and attachment size restrictions removed the barriers for sending decent sized files via traditional email. As of June 2007, popular services like Google's GMail and Windows Live Hotmail offer 2 GB of free space. Yahoo Mail even went as far as offering unlimited storage. [14] For larger files such as bundled music albums and films that exceed the maximum attachment caps, users turn to dedicated file uploading services like YouSendIt. After the file is uploaded, a notification is sent to the intended recipient with a retrieval URL. Recently, programs like MyTunes managed exploit sharing capabilities of the widely used music player iTunes, allowing users on the same local network to share their music libraries. All in all, in these proposed cases, the user is obtaining material from known, local sources on an personal basis via the internet.

P2P networks

Highlights: Kazaa, eMule, LimeWire, the original Napster

Peer-to-peer (P2P) networks comprise of computers across the internet linked together with special file sharing protocols implemented by different P2P programs. Popular protocols vary by two qualities: centralization and structure. Centralized P2P network protocols, like one used by the first version of Napster, rely on dedicated severs to record client information and store pieces of the shared data. Newer, decentralized P2P networks like FastTrack (used by popular P2P programs like KaZaa and Grokster) depend on individual clients to relay information; each computer on the network can act both as the sender and receiver of traffic. The way in which computers are connected inside of a P2P network determines its structure. When a client joins unstructured network, the computer only has access to files shared by known sources, barring access from the rest of the computers. Trying to locate a rare file is a lot harder because of the connection limitations. Structured P2P networks have streamlined methodologies for unique searches. Using technologies like distributed hash tables (DHT), it is incredibly efficient to find a file on the other side of the web. The beauty of P2P protocols and client/server networks relies on its user base. The combined processing power and bandwidth capabilities of these networked computers provide unprecedented levels of digital resources. With enough contributers, people can easily find and quickly download every piece of digitized work ever made.

The original Napster was the first P2P program to achieve mainstream status. In 2001, the final ruling of the case A&M Records, Inc. v. Napster, Inc. found this file sharing giant liable for illegal "contributory infringement of plaintiff record company's copyrights." [15] Even though Napster was consider a P2P program, it worked in a far more centralized way. The A&M Records' lawyers had incontestable evidence showing the defendant's role in facilitating copyright infringement, for clients depended on servers to talked to other clients. After Napster's demise, other P2P applications using newer, more efficient P2P protocols found their place in this industry. Popular programs like KaZaa (FastTrack protocol), eMule (eMule 2000 protocol), Limewire (Gnutella protocol) employed more decentralized and more structured ways of data exchange. These iterations of the original design, thus in a sense, are considered true peer-to-peer technologies.

Torrent networks: Torrent indexers, trackers & clients

Highlights: ThePirateBay, MiniNova, µTorrent, Azureus

The Torrent network is another file sharing alternative. BitTorrent was developed by programmer Bram Cohen during the summer of 2001. [16] The main quality that sets BitTorrent apart from other P2P technologies is its ability to efficiently transfer large amounts of data quickly and efficiently. When a user downloads something via traditional P2P means, most of the data usually comes from a couple of individuals who are sharing the same completed file. Unlike KaZaa, eMule, and LimeWire, all data on the torrent network are broken up into small pieces and simultaneously shared by huge pools of users. Each individual's Torrent client has the ability to connect to hundreds of other clients who are sharing pieces of the same sought after file. The relationship between clients are symbiotic. In order for computers to download pieces of a file, they too have to share similar pieces with other computers. This forced reciprocity and piece-wise sharing technique provides noticeable boosts productivity and speed. A 2004 report from CacheLogic claimed "Online movie trading is skyrocketing, but onetime leader Kazaa is tumbling in use" Andrew Parker, CacheLogic's founder and chief technology officer said, "The overall level of file sharing has increased. Users have migrated from Kazaa onto BitTorrent." [17] Because computer users are increasingly downloading larger files like movies and software, in the first few years of this decade, P2P traffic on the internet surpassed all other types of data. [18]

There are three integral components of the Torrent system; each provides a specific function that is uniquely independent of the others. Torrent indexers like ThePirateBay and Mininova stores databases full of ".torrent" files which contain the locations of both public and private torrent trackers. These tracker servers help client computers loaded with compatible torrent programs like µTorrent and Azureus connect with other candidates from all across the web. While anyone can download from public trackers, there are exclusive invite-only private trackers that provide even faster connections. Clients act as individual nodes on the network; their main job is to communicate with other clients to trade copied pieces of the requested file until all the pieces are downloaded. An user commences a download by loading a small ".torrent" file retrieved from a torrent index site into the torrent client. The client then communicates to the given server(s) and retrieves a list of IP addresses where pieces of the same file are being hosted. In case a server is down or not responding, clients also have the ability to use DHT (Distributed Hash Table) and PE (Peer Exchange) technology to find the locations of other clients without the assistance of trackers.

Warez networks

Highlights: Astalavista.box.sk, Cracks.ms

Warez is technical slang that stands for a broad spectrum of online counterfeit content. Ripped computer programs, music, movies, books and any copyrighted content published in a organized but illegal fashion can be considered Warez. Underground organizations called "release groups" operate on a minute by minute basis in constant search for new, unreleased music albums and features film to push on the web. In a 2005 Wired Magazine article, Erik Malinowski describes the five step "trickle-down file-sharing" system. [19] He divides up the piracy chain into the insider, the packager, the distributor, the couriers, and the public. According to Malinowski, majority of the high quality content that reaches the internet prematurely originate from insiders. Appointed screeners, workers at optical disk manufacturing plants, and moles within the production industry feed unreleased copies of albums, films, or computer programs to these release groups. In return, these people are usually provided with monetary contributions and access to terabytes of high quality media stored on the release groups' servers. Once a copy of unreleased media content gets into a release group, packagers working non-stop to encode and compress the content into smaller sized, easily transferable files. The content is then stamped with the release group's name or logo, zipped with a NFO file or (information file) giving credit to a release group, and passed on to the distributor. On the digital end, most release groups have relationships with "topsites" or "highly secretive sites on the top of the online distribution pyramid." [20] When a topsite operator publicizes the file on its networks, couriers immediately begin pushing the package to more accessible P2P and Torrent networks for the public to access. On the physical end, release groups can simultaneously sell copies of unreleased content to disc piracy manufacturers all around the globe. Immediately, people in the counterfeit disc business will begin mass producing copied CDs/DVDs to sell to audiences on the streets.

Even though most insiders and people associated with release groups do not know their acquaintances in person, members of these select organizations develop strong bonds with each other, for getting a new piece of media into the public takes teamwork and precision. The race to be first at offering the latest copyrighted content stirs up immense amounts of competition among release groups. Once a copy of an publicly unavailable content reaches the web, the value of such file or files drops close to zero. Over the years these underground networks of moes, hackers, crackers, and rippers were dubbed "The Scene." [21]

Besides producing ripped films and other media, release groups also have been known for cracking licensed software. Instead of insiders, the these groups depend on software crackers to supply the goods. Reverse engineering programmers spend their days trying to figure out how to defeat embedded license protection mechanisms. Crack/CD-key aggregators like Astalavista and Cracks.ms store hundreds upon thousands of key generators, patches, and other forms of cracks for a wide range of software. Users who can't find a prepackaged release from BitTorrent often resort to this manual search method. Though, one must wade through a lot of pornographic content, spyware exploits, and virus ridden files before finding anything useful. For amateur computer users, the risk of endangering their computers' integrity by exposing them to these malicious sites is too great; thus, they turn to traditional legal means.

Web mediums: Media sharing & aggregation

Highlights: Tv-Links.co.uk, PeekVid, YouTube, Veoh

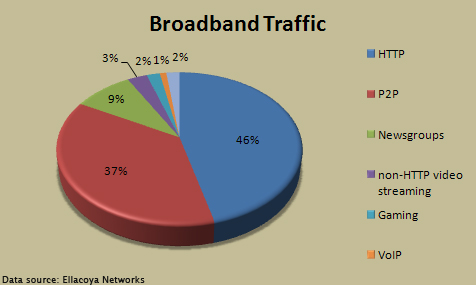

With help from YouTube, online video sharing and streaming websites have caught on as top accessed online services among mainstream internet users. The analysis of internet traffic has always been a great way to measure the popularity of different protocols. For example, typical web browsing will amount to HTTP traffic. (When browsing the internet, notice websites usually have the letters âHTTPâ in front of the URLs.) Likewise, accessing FTP servers will generate FTP traffic, using P2P networks such as KaZaa or BitTorrent will generate P2P traffic, and so forth. For the first few years of the twentieth century, P2P data has dwarfed other forms of transferred traffic largely due to the immense popularity of music and video sharing. In a 2007 study, however, Ellacoya found âfor the first time in four years, P2P traffic finally fell behind HTTP. Chalk it up to YouTube and other Internet video sharing sites. The surge in HTTP traffic is largely a surge in the use of streaming media, mostly video.â Specializing in IP service control, Elacoya said, âBreaking down the HTTP traffic, only 45 percent is used to pull down traditional web pages with text and images. The rest is mostly made up of streaming video (36 percent) and streaming audio (five percent). YouTube alone has grown so big that it now accounts for 20 percent of all HTTP traffic, or more than half of all HTTP streaming video." [22]

YouTubeâs popularity comes with a cost. "New web sites are making it even easier for anyone who can click a mouse to access copyrighted content across the net. You no longer need to know your way around IRC or understand what a .torrent file is. Instead you can just stream them over any number of social video sites." [23] Since there are little to no physical restrictions that prevent users from uploading copyrighted content, individuals often times believe sharing an episode of Family Guy or Friends on YouTube is just. While some companies like CBS allow segments of their popular shows to be streamed online as means of free advertising, other TV stations and media networks retaliated in full force, taking Google's YouTube and Google Video to court. Since the start of the lawsuits two years ago, Google has "agreed to remove more than 100,000 video clips produced by Viacom properties, including MTV Networks, Comedy Central, BET and VH-1, according to a YouTube statement." [24] Of course without an extensive filtering system, people often find ways to sneak copyrighted content onto these services. A recent report titled "Is Google Promoting Video Piracy?" form the NLPC (National Legal and Policy Center) found "Google Video hosted apparently pirated copies of current major films as "Sicko" and "Evan Almighty." Both were posted without the permission or knowledge of the copyright owners. This follows a lawsuit against Google by media giant Viacom seeking $1 Billion in damages." [25] As of June 12th, 2007, Google is preparing to test it's video screen technology that will hopefully flag potential copyrighted material once they are uploaded. [26]

Other online video hosting companies like Veoh, VideoEgg, DailyMotion, GoFish are also stepping up their anti-piracy awareness in fear of lawsuits. Because of this, pieces of copyrighted content are scattered in random locations across the net. Video aggregation sites like the infamous PeekVid and recently popular TV-Links.co.uk compile these hard to find links into one location. In return for these services, these webmasters earn revenue from the pervasive amount of advertisements on their websites.

Conventional means: FTP, Webservers, IRC, USENET

Owners of web and FTP servers have the ability to publish copyrighted content accessible by the internet audience. Since most of these servers are rented by individuals for personal or small business use, these methods of distribution are much slower than dedicated file hosts such as YouSendIt. If something popular is discovered to be hosted on a non-password protected server, the surge in bandwidth during a short period of time can easily cause a system crash. Most of these uploaded copyrighted content stored for either backup or limited sharing among known relations. Unfortunately, search bots or page crawlers such as Googlebot, frequently indexes pages containing these files. There are certain searches techniques one can use to pull up copyrighted content such as songs, movies, or TV shows. Using IRC (Instant Relay Chat) Channels and USENETs to acquire copyrighted content still can be done, but definitely have fallen below main stream usage. Even though both methodologies prove to be extremely fast ways to download files, both require above average computer know-how and connections within online communities that share such content.

|

|

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Every copyable form of media, from mass printing back in the 15th century to the cassette tape technology in the second half of the 20th century, was illegally exploited for profit. Before the popularization of digital formats and the increased accessibility of the internet, illegal distribution of physical copyrighted material was the prevalent form of piracy. Today's global physical piracy can be categorized into three sections: individual license violation, corporate to end-user violation, and reseller/distributor violation.

Individual license violation

The simplest form of physical piracy is committed by the everyday computer user. Factoring intentionality out of the equation, these transactions involve little to no net profit and is pertinent to all kinds of media. People who do not understand or do not care to understand licensing for a specific media product oftentimes overuse or misuse their given rights. Of course, different forms of media have different user agreements. A list of things one can and cannot do with a purchased DVD differs from what one agrees to when installing a computer program. True, some of these rights are innate. The ability to watch a DVD or start Microsoft Word whenever you want comes without question prepackaged in the original deal. After all, one is paying money for ownership.

Many restrictions concerning duplication and distribution, however, are not explicitly outlined in the perplexing user agreements. For example, installing single copy of a popular software on multiple computers is a perfect example of license overuse. The SIAA dubbed this behavior "softlifting." [27] Other forms of manipulative techniques for personal financial benefit are listed as follows. Falsifying one's identity to obtain additional upgrade features or manufacturer discounts, using academic or non-retail software for commercial purposes, copying/distributing licensed software and locked media with immediate relations are all considered individual license piracy. Because these interactions are on a local level, authorities rarely bother to trace this form of physical piracy.

Camcording is a huge issue the movie industry has to face on a daily basis. The term refers to the process where individuals capture featured films with portable recording devices. According to the MPAA, "ninety percent of pirated copies of movies are still playing in theaters. Once a camcorded copy is made, illegal movies often appear online within hours or days of a movie premiere." [28] Recently, stronger legislation have been put in place to discourage people from committing this crime. President Bush in 2005 signed the Family Entertainment and Copyright Act into law. It "makes camcording in a theater a federal felony and establishes new penalties for pirating works that have not yet been released commercially. First-time violators can be sentenced from up to three and five years in prison, and fined up to $250,000 for these kinds of crimes." [29] While some of the amateur camcorder pirates keep these recordings for at home viewing pleasure, most confront the risk for profit or other forms of personal gain. As mentioned before in a previous section, if the moles inside the movie industry do not leak the screener before a specific movie hits theaters, the release groups than depend solely on these lower quality camcorder versions to publish on the internet. These pirates also sell these recordings to "illicit source labs where they are illegally duplicated, packaged and prepared for sale on the black market, then distributed to bootleg dealers across the country and overseas. Consequently, the film appears in street markets around the world just days after the US theatrical release and well before its international debut." [30] In this case, these camcorder pirates can also be categorized in the reseller/distributer group because they are also a vital part of that physical piracy chain.

Corporate to end-user

Corporate to end-user piracy involves the misuse of software licensing within businesses and other organizations, such as schools, universities, and government funded programs. Unlike individual license piracy, the misuse of software licenses in this case are backed by the administrations representing these respective institutions. In the process of increasing productivity by installing better software while keeping costs to a minimum, the higher ups sometimes overlook the obvious legality issues behind allowing the proliferation of intangible things like computer programs.

There are three main forms of corporate piracy. The first form involves installing single-licensed software on multiple computers. Like individual license overuse, when company IT departments hands out free copies of Office 2007 or Adobe Photoshop to their employees, the end-users are benefiting at the loss of Microsoft and Adobe. Many organizations chose to buy volume licensing for expensive software titles. Because it is fiscally inefficient to purchase a copy of software for every single employee, companies oftentimes use keyed servers & keyed programs to reduce costs. This way, only a set amount of licenses needs to be bought for a bigger pool of users; however, thanks to the management of the keyserver, only that set number of users can access this program at any given time. Client-server overuse occurs when this keyserver fails to control the number of people who can access a program at the same time. Finally, hard-disk loading means illegally installing licensed software on computers' hard drives before they are given to employees or sold to costumers. Again, in this case, the end-user is put in a situation where they are unaware that their usage of certain computer programs is unlawful.

Because corporate to end-user piracy improves profit margins (or increases losses from the perspective of the programmers) at a much larger scale than the illegal individual sharing of copyrighted content, the software companies have more incentives to seek compensations. Anti-piracy organizations specializing in hunting down software pirates such as the SIIA (Software & Information Industry Association) and the BSA (Business Software Alliance) have been assisting today's most prominent software companies like Apple, Microsoft, and Adobe fight this and other types of piracy for quite some time now. While both the SIIA and BSA publish reports concerning the latest piracy statistics worldwide, the SIIA even has elaborate online form for company whistle-blowers to report the misuse of software licensing within their organizations. There is even a up to $1 million reward depending on how the pervasiveness of piracy. [31]

Reseller and distributor

Over a period of 18 months, LEK surveyed 20,600 movie consumers from 22 countries and found "62 percent of the $6.1 billion loss (reported by the movie industry) result from piracy of hard goods such as DVDs, 38 percent from internet piracy." [32] Despite recent telecommunication advances and increasing numbers of broadband computer users, compared to online digital piracy, physical piracy still plays a larger role in the global piracy market. The reason for this phenomenon is largely due to the well built infrastructure and well engraved ideologies in select regions of the world. People in countries like Armenia, Moldova, and Azerbaijan, where over 90% of the software are obtained illegally, do not believe in paying for software. [33] Lifetime habits, after all, are hard to change. Of course, larger piracy-ridden countries like China, India, and most of Southeast Asia also play huge roles in fostering the continual growth of this illegal act. Resellers and distributors of copyrighted material contribute to the largest portion of today's worldwide physical piracy.

Unlike corporate and individual piracy, resellers and distributors work in closely knit, well built networks of sellers and buyers, all of whom have the ultimate profit seeking goal in mind. In a way, these collections of physical pirates analogous to the previously discussed online release groups. With speed and style in mind, these people deliver top notch replications of the latest unreleased content in a matter of hours after something is leaked. Reseller and distributor physical piracy can apply to all different forms of media. From software to movies, from music to games, all digitally formatted content have the risk of being physically copied and sold. Selling copied or counterfeit software for a reduced price as street vendors or in counterfeit stores, running unlicensed movie theaters or rental facilities, illegal direct resell and auctions of improperly licensed media are all considered physical piracy.

Case Study #1: What is wrong with this picture?

In this eBay auction, the seller is attempting to sell a valid Windows OEM license. He states in the description of the auction "the computer died but your winning bid the license can live on. Since the original system died, this Windows XP Home Edition license can be activated on another system. This is an auction for one license key only. No software is included. It is branded Toshiba but will work on any system. You may need to call Microsoft's 800 number to activate." Whether or not the seller made a genuine offer is besides the fact, for when one posts the a readable picture of the serial number, what is there left to "purchase"? $39.95 is a heavy price to pay when one can just copy down the number. Surprisingly, there were 12 bids on this auction when this screen shot was taken.

|

|

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

By understanding methodologies behind these commonly used utilities and practices, we can have a better understanding of piracy's role in the lives of digital natives.

Piracy & Law

The chain reaction that instigated copyright regulations dates back to the fifteenth century. Gutenbergâs printing press marked the beginning of a new era of information distribution. True, this device facilitated the mass production and dissemination of human knowledge; however, it also carried repercussions. The formerly tedious task of duplication by hand was sped up to a rate that warranted tighter controls. When this technology arrived in England, the "need for protection of printed works was inevitable." [34] In 1710, the English Parliament passed the first official law concerning copyrights. The Statue of Anne "established the principles of authorsâ ownership of copyright and a fixed term of protection of copyrighted works." [35] Almost three hundred years have elapsed since this passing of this statue. Although some ideological remnants still remain, todayâs US copyright law "has been revised to broaden the scope of copyright, to change the term of copyright protection, and to address new technologies." [36]

Present day US copyright regulations stemmed from the first days of nationhood. When Americaâs founding fathers composed the United States Constitution in 1787, they gave Congress the power "to promote the progress of science and useful arts, by securing for limited times to authors and inventors the exclusive right to their respective writings and discoveries." [37] This line of text in Article I, section 8 bestowed upon the State fundamental rights to a monopoly over the copyright industry. It was the governmentâs job to asset, distribute, and control all copyrights. "The First Congress implemented the copyright provision of the U.S. Constitution in 1790," modeled quite similarly to the Statue of Anne. [38] Since then there had been three major revisions which occurred in the years 1870, 1909, and 1976.

With arrival of the digital age, Congress amended the copyright act to "prohibit commercial lending of computer software" in 1990. [39] This revision did not solve all the problems, for technology was evolving at a rapid pace. Computer savvy individuals were finding ways to bypass government copyright regulations. For example, under copyright laws up to the No Electronic Theft (NET) Act of 1997, people who intentionally distributed copyrighted software without receiving monetary benefits could not be prosecuted. The NET Act amended this loophole. [40] Following NET, 1998 was also a big year for copyright in the technological realm. The â98 Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) laid the foundations for RIAAâs cases half a decade down the line. Besides making "it a crime to circumvent anti-piracy measures built into most commercial software," the DMCA most importantly "limits internet service providers from copyright infringement liability for simply transmitting information over the internet." [41] Known as the "safe harbor provision," DMCA Title II (OCILLA) creates a "safe harbor" for internet service providers (ISPs) from being liable for content stored or transmitted via their servers as long as they take swift steps to remove the copyrighted content when asked. This Online Copyright Infringement Liability Limitation Act also gave plaintiffs the right to subpoena user information from the ISPs to carry out individual lawsuits.

As of January 2007, there are two portions of the United States code detailing domestic copyright regulations. USC Title 17 provides a comprehensive breakdown of every copyright guideline while section 2319 of Title 18 lists possible consequences for criminal infringement of a copyright. Under these laws, not everything conceived by the mind is eligible for copyright. According to chapter 1 section 102 of Title 18, the United States copyright law protects "original works of authorship fixed in any tangible medium of express." [42] This includes "literary, musical, dramatic works, pantomimes, choreographic, pictorial, graphic, sculptural works, motion pictures and other audiovisual works, sound recordings, and architectural works." [43] Ideas, not yet formulated on such "tangible mediums," thus, do not qualify. When a work is classified as copyrighted, section 106 of chapter 1 gives only the proper owner of the work the rights to reproduce, prepare derivate works, distribute, publicly perform, and publicly display the creation. In addition, these exclusive rights must be granted by the owner in order for third parties to use the copyrighted material.

When one or more exclusive rights such as the ones listed above have been breeched by an individual or a corporation, this respective party is considered to have committed a "copyright infringement." Although there are limitations to the power of these exclusive rights, such as cases where the violation has been deemed legitimate under the four conditions of "fair use" or other exceptions for special educational organizations, in most cases where the copyrighted content has been duplicated and/or distributed without the prior consent from the owner, infringement most likely occurred.

Consequences for infringement vary from case to case. The prosecution may choose to sue for measures at its discretion; however, the US Code does outline maximum and minimum sentences for different scenarios. Section 504 for Title 17 allows for the plaintiff to charge the defendant for actual and statutory monetary damages. Detailed evidence proving losses directly linked with the case is needed to recover actual monetary damages. As for statutory damages, the allowable compensation range from $200 to $150,000 per each infringed copyrighted work. If the prosecution can further prove that the defendant has used the copyrighted material either "for purposes of commercial advantage or private financial gain" or have reproduced or distributed content "which have a total value of more than $1,000," criminal charges found in section 2319 of Title 18 may apply. According to this section of US Code, if the defendant has been found in violation of copyright for personal financial gain, the maximum sentence is 5 years imprisonment for the first offense. Similar subsequent offenses carry 10 years imprisonment per offense. If the defendant has been found in violation of copyright for which the content had a total value more than $1,000, the maximum penalty is 3 years imprisonment for the first offense and 6 years for each additional offense in the future. These criminal charges are additions to monetary damages incurred from section 504 and even possible attorney fees of the plaintiffâs party from section 505 of Title 17.

Fair Use

The United States Fair use doctrine is a method of defense that can be employed when an individual is being accused of copyright infringement. Fair use allows for legal incorporation of copyrighted content in a new piece of work without prior agreement from the original author. [44] United States Code, Section 107, states usage of another's work "for purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching (including multiple copies for classroom use), scholarship, or research, is not an infringement of copyright." However, because this law can be applied to situations with drastically different circumstances, the ruling of a specific case is hard to discern. To solve this problem, Section 107 "Limitations of exclusive rights" lays down four factors to be considered when judging the validity of Fair use: "the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes; the nature of the copyrighted work; the amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole; and the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work." [45] The judge presiding over a case involving Fair use must weigh these four factors in a balancing test.

| Fair use | Copyright infringement |

|---|---|

| Advances public knowledge | Fails to do so |

| Transformative use | Less transformative use |

| Little to no commercial use | Commercial use |

| More creative, less purely factual | Less creative, more purely factual |

| Copying published works | Copying unpublished works |

| Small portions of the work copied | Huge portions of the work copied |

| Derivative work does not harm potential market | Derivative work harms potential market |

There are four main factors that determine whether or not a case can qualify as fair use. Factor one -- "purpose and character" states, if the usage of a work advances public knowledge, is very transformative, and has little to no commercial purposes, then it is easier to argue for fair use. Factor two -- "nature of the copyright work" states, more creative, less purely factual usages of published works have stronger protection against copyright infringement. Copying unpublished works without the author's consent usually weakens the defendant's case for fair use. Factor three -- "amount and sustantiality of portion defendant used" is more straightforward than the first two factors. The larger the portion of copyrighted work used, the more prone the ruling will be in favor of copyright infringement and vice versa. The final factor -- "effect of defendant's use on potential market of copyrighted work" plays the most important role in determining the right to Fair use. If the derivative work endangers the original work's potential market opportunities, then the court will most likely be in favor of the prosecution. Criticism or parodies that may put the original work in a bad light are allowed even though it might damage the potential market. [46]

Piracy Among Digital Natives

Reasons for Piracy

- Saving time & money

- Digital natives are used to having immediate access to digital media. They aren't familiar with having to go to a record store and buy the latest CD or even having to record on a VCR a favorite show -- they can get the materials almost as quickly as they come out.

- Supply & demand + youth popularity

- Method of self expression

- Curiosity & standing trends

- Weak repercussions

- Online disinhibition effect

- Anonymity

Online Piracy: The Ultimate Generation Gap, 2003

- FOX News report on youth piracy

"The generation before us had to pay for music," said recent college grad Joshua, 24, of New York City. "Now you have no reason to purchase the music or movie in physical form. Everything is digital."

"Kids really don't care," said college freshman Ben, 18, of Upper Nyack, N.Y. "We all copy music and download movies because the chances of them cracking down on us specifically are slim."

"The lawsuits are both futile and counterproductive," said Fred von Lohmann, senior staff attorney at the Electronic Frontier Foundation. "Not only will they not stop file sharing, but they'll alienate customers."

"We're hopeful we haven't lost this generation," said Bob Kruger, enforcement vice president of the Business Software Alliance, which fights software piracy.

"It makes me feel kind of bad â like, 'oh no, I'm doing something illegal,'" said Melissa, the Florida teen. "I'm probably downloading a little less."

Charismatic Code, Social Norms, and the Emergence of Cooperation on the File-Swapping Networks

- Strahilevitz's analysis of P2P networks

"Virtually everyone who participates in one of the file-swapping networks is breaking the law in the process. Ordinarily, people are unlikely to trust lawbreakers, especially anonymous lawbreakers. Yet a remarkable sense of trust permeates these networks. ... [I]t is possible to observe significant levels of cooperative behavior, very little by way of destructive behavior, and substantial trust among the anonymous users of these networks. Furthermore, the networks have survived and thrived largely because of their users' dogged willingness to engage in unlawful activities."

Charismatic code-- "a technology that presents each member of a community with a distorted picture of his fellow community members by magnifying cooperative behavior and masking uncooperative behavior."

- "the applications harness the actual members of the community to become actors for norm enforcement purposes by magnifying the actions of those who cooperate and masking the actions of those who do not"

- "the applications act as a substitute for the community of actors and enforcers, inculcating in their users those norms most likely to lead to the success and expansion of the networks"

- "the applications act as a substitute for the community of actors and enforcers, inculcating in their users those norms most likely to lead to the success and expansion of the networks"

Distorted image-- (Gnutella network) "Charismatic code is the primary tool in that effort. Because of the way the networks are structured, the actions of those who share content are quite visible, while the actions of those who do not share content are virtually invisible. ... The architecture of the networks is such that although many users on the networks do not share, the networks create an appearance that sharing is the norm. This dynamic - the magnified visibility of sharers and the invisibility of non-sharers - exists on every successful file-swapping application I have seen."

"By the same token, these affinities normalize file-swapping: Members of the file-swapping networks stop being identified as 'rogue software pirates' and start being identified as 'people who, like me, have excellent musical taste.'"

Reciprocity-- "Technologies that magnify cooperative behavior and mask uncooperative behavior can succeed by tapping into deeply held social norms. In this instance, the file-swapping networks have been successful in large part because they have managed to tap into internalized norms of reciprocity. ... The networks' creators are drawing upon reciprocal intuitions that their users are likely to possess. Once again, the software is designed to exploit those intuitions."

- MusicCity and KaZaa's upload/download page

- Forced reciprocity implementation in 2001

Piracy & Tech Culture

Newly developed technologies of the last decade are giving users unprecedented freedom and control over media. Since embracing novel technologies and keeping current with the latest trends are crucial to the cultural standard of digital natives, such innovations provided the foundations for today's piracy.

- Software innovations

- Fast, efficient transfer protocols

- User friendly file sharing applications

- Online advertisement system

- Software communications boom

- Hardware innovations

- The personal computer

- MP3 players

- Portable multimedia players

- Storage medium technologies

- "Hardware synergy"

At heart, below the layers of accessories and fancy gadgets, the youth generation of today are not so different from the previous generations. Your typical teenager has a rebellious streak. Such teenage mentality drives counter-mainstream adult ideologies, which incites piracy.

- Newspaper article concerning Canadian piracy

"Hollywood can help itself by doing business with iTunes Canada and providing a library of legal content to download. That, and some stronger legislation from Ottawa, would go a long way to keeping us honest."

"Based on a survey polling wired Canadians in February, we not only bootleg directly from the screen, but we also like to download pirated booty - a lot. A whopping 93% of those downloading movies in this country are doing so illegally. And it's not just tech-savvy teenagers. Nearly 50% are over age 46."

"And pinning it on in-theater theft seems to fly in the face of a 2003 study done by AT&T, which concluded that Hollywood was prone to insider attacks, which resulted in leaked screener copies of 77% of 312 movies studied."

"It's commonly known that Montreal is a hot spot," says Dewolde. "In Canada there's no law against camcordering, so it's hard to stop these guys. The worst they can get charged with is trespassing. It's a huge issue."

"At first blush, it looks as if Canadians are more liable to piracy than their counterparts in the U.S.," says Phil Dwyer in a release. "In reality, many of these illegal downloads are taking place because of the lack of legal alternatives. The market is more mature in the U.S., and the experience there shows that if you give consumers a legal, convenient and fairly priced alternative to piracy, the majority will use it."

"We're pretty polite pirates. Give us a legal way to download movies and you'll see a sea change. No doubt many people have looked longingly at the growth of content on iTunes before downloading that torrent."

- Transcript of a round table discussion about counterfeiting in general

Roz Groome - "What has been highlighted are the different strains of harm that are going on. Physical harm, financial harm and social harm - the connection between counterfeiting, piracy, organised crime and other antisocial behaviour. Then also, there is economic harm for the industries and to the Treasury, because no tax flows back on counterfeit goods. People need to realise that they are not just lining the pockets of the rich and famous. For every musical hit there are ten failures and most musicians do not earn what Robbie Williams earns. In terms of creativity, and in terms of ensuring that consumers pay for the product, it is important to ensure that the money flows back to the people who are responsible for creating it and many of those people will not be rich and famous."

Michelle Childs - "Jo has done some interesting research about the motivation of consumers to purchase counterfeit goods. It raises some interesting competition questions. When you are talking about motivation to buy fake DVDs, 56 per cent of respondents bought them because they wanted to see a film as quickly as possible. So perhaps consumers are giving market signals. Perhaps they are saying that some of the old ways of doing things, such as having windows for releasing DVDs in different markets or only releasing music in certain formats, are not what they want and are not going to work."

Jo Bryce - "The answer might be to fill that market gap, rather than to get tough with criminal sanctions."

"If anything, they seemed to believe that the rip-off that was taking place was in the price charged for legitimate goods, rather than the counterfeit ones."

Mike Smith - "The counterfeit manufacturing and duplicating of CDs and DVDs and selling them through markets is highly visible. But on the internet, your children, 17 or 18 year olds, are swapping files and it is not so freely visible."

Mike Smith - "These young people are music enthusiasts, so it is ironic that, by swapping and downloading these music files, they are hacking into the profits of the record companies and taking money that should, by rights, be paid to the songwriters and artists."

Mike Smith - "There is an argument that the future may perhaps not consist of record sales, except in a more niche, particularly high-fidelity market. Essentially music may be seen as a commodity, as a utility, as something that you get streamed to your mobile phone and that you can access constantly, wherever you go. Maybe you will pay a monthly subscription and get your music constantly coming into your life, so that it almost seems like a free commodity. What the record companies need to work out is how the people that are still manufacturing and marketing most of that music also manage to get paid for it - how our artists get paid and the people writing the songs get paid."

Mike Smith - "No. So there is a degree of education to be done. There is also, to a degree, an acknowledgement that we are trying to turn back the tide and we cannot; itâs too late. We need to acknowledge that this is possibly the future and we need to adapt our business practices to reflect that."

Roz Groome - "They will not, but I tell you who is concerned: their parents. We have conducted a massive litigation campaign against egregious uploaders. These are not people downloading, they are uploading. They are behaving like mini free retailers. They are making available thousands of files to millions of people, constantly. Everything is available on filesharing software; everything is out there. I have spoken to the parents and they are horrified. They have copied their CD collections on to their computers to enjoy them, to put them on their iPods or whatever. Then their children have come home from school and downloaded some file-sharing software on to the family computer system, which has then made available to the world their entire CD collection. Incidentally, it is not just their CDs but anything that happens to be in their shared drive. This can include the family photographs, the Expedia receipts; I have seen bank account details, it is all there. That is where consumer education needs to come in. The people doing this need to see the harm it is causing."

Jeff Randall - "Once you can access music for free, people assume it is free. They do not think it through and they do not really care. That would be my view. It is a terribly cynical view, but the music industry, clearly, is facing that problem because that is what people are doing."

Mike Smith - "The music industry has to adapt in order to survive. What we are trying to do with BPI is legitimate protection of our copyrights. We have to do that, but the world is changing dramatically, and the way that a record company gets its revenues is not going to be reliant solely upon sales of records. We are going to have to become music companies, not record companies, and we may come to look upon records as being a loss leader."

Mike Smith - "All this could be a positive force. The internet could be the best thing that ever happened to the music industry."

Repercussions

For those who download through peer-to-peer (P2P) networks, the MPAA and RIAA have brought up the many potential risks one faces when accessing these servers. In the parental resources section of the MPAA website, the organization warns about four dangers of P2P programs: âSubject users to pornography, open personal files on your home computer to strangers online, increase the risk of a computer virus, lure kids into illegally downloading movies and music, which can lead to jail time and finesâ [47].

The first three concerns the MPAA notes are typical risks users face when acquiring content through such systems. Many online hackers exploit the P2P search system for monetary gains. By analyzing the trends of high demand movies or music, these profiteers simply manipulate the file names of the viruses and malware they want to spread to match the names of popular song artists and movie titles. Average users who are unaware of these tactics often times are gullible enough to execute these masked programs without realizing the fileâs identity. Even the ever-popular P2P software Limewire admits to the existence of viruses and other harmful material on their networks. In its online FAQ, the programmers warn Limewireâs users, âif you attempt to download a virus-infected file using LimeWire, you will be vulnerable to any viruses contained in that fileâ [48].

In addition to harmful materials one can download, many of these free P2P programs are packaged with third party spyware programs that will slowly but surely retard the speed and reliability of a computer. Like the infamous AOL installation back in the day, a handful of these shareware clients come bundled with various harmful third party applications. By means of a deceptive installation wizard or simply packing other software with the executable, oblivious individuals get much more than what they originally wanted.

Finally, users face the possibility of legal consequences due to copyright infringement. Since most P2P search requests will pull up media across the whole copyright spectrum, the MPAA does not want children to get the impression certain copyrighted content can be acquired without charge. The legal consequences does not discriminate by age. From a warning to a petty fine of $200 to $150,000 and 5 years in jail, the potential cost of piracy is very real [49].

Solutions

Eliminating piracy in the foreseeable future is a next to impossible task. There will always be people seeking ways to circumvent laws for a variety of reasons. There is hope, however. Even though wiping out piracy is not feasible, reducing this theft of digital material can be accomplished.

Raising Awareness

- Getting the message across to the new generations of Digital Natives

It is human nature to want to fit in with the rest of the populace. For example, if the majority of Trevorâs peers does not condone or commit piracy, it is highly unlikely Trevor will spend Friday nights at home downloading the latest blockbuster for he will be at the movie theatre watching the film with his friends. Thus, it is necessary to embed piracyâs immoral ideologies as early as possible in the heads of rising digital natives.