Current Methodologies

Advent of the internet and the rapid increase of personal computers means more people than ever before have the capability to share information online. Though these advancements give users unprecedented access to the world's data, enforcing proper copyright restrictions while allowing justifiable sharing freedoms have not been attained. Thus, many have pointed to these new technologies as the facilitators of so-called "digital piracy." Today, users employ many different applications and services to illegally transfer copyrighted material. Factoring intentionality out of the equation, this section aims to introduce these online trade tools.

Local sources

Highlights: Live Messenger, E-mail, YouSendIt, MyTunes

The easiest and often times fastest way a person obtains copyrighted materials is from local, direct sources. Friends, family members, classmates -- an individual's immediate relations are commonly the people one asks when in need of a song, copy of a TV show, or a recent movie. Popular chat software like Microsoft's Live Messenger, AOL's IM, even Yahoo Messenger all support some form of a file transferring mechanism allowing these exchanges to happen. A few clicks and a potentially copyrighted file is on its way. Thanks to the recent milestones in the email industry, ever increasing account quotas and attachment size restrictions removed the barriers for sending decent sized files via traditional email. As of June 2007, popular services like Google's GMail and Windows Live Hotmail offer 2 GB of free space. Yahoo Mail even went as far as offering unlimited storage. [1] For larger files such as bundled music albums and films that exceed the maximum attachment caps, users turn to dedicated file uploading services like YouSendIt. After the file is uploaded, a notification is sent to the intended recipient with a retrieval URL. Recently, programs like MyTunes managed exploit sharing capabilities of the widely used music player iTunes, allowing users on the same local network to share their music libraries. All in all, in these proposed cases, the user is obtaining material from known, local sources on an personal basis via the internet.

P2P networks

Highlights: Kazaa, eMule, LimeWire, the original Napster

Peer-to-peer (P2P) networks comprise of computers across the internet linked together with special file sharing protocols implemented by different P2P programs. Popular protocols vary by two qualities: centralization and structure. Centralized P2P network protocols, like one used by the first version of Napster, rely on dedicated severs to record client information and store pieces of the shared data. Newer, decentralized P2P networks like FastTrack (used by popular P2P programs like KaZaa and Grokster) depend on individual clients to relay information; each computer on the network can act both as the sender and receiver of traffic. The way in which computers are connected inside of a P2P network determines its structure. When a client joins unstructured network, the computer only has access to files shared by known sources, barring access from the rest of the computers. Trying to locate a rare file is a lot harder because of the connection limitations. Structured P2P networks have streamlined methodologies for unique searches. Using technologies like distributed hash tables (DHT), it is incredibly efficient to find a file on the other side of the web. The beauty of P2P protocols and client/server networks relies on its user base. The combined processing power and bandwidth capabilities of these networked computers provide unprecedented levels of digital resources. With enough contributers, people can easily find and quickly download every piece of digitized work ever made.

The original Napster was the first P2P program to achieve mainstream status. In 2001, the final ruling of the case A&M Records, Inc. v. Napster, Inc. found this file sharing giant liable for illegal "contributory infringement of plaintiff record company's copyrights." [2] Even though Napster was consider a P2P program, it worked in a far more centralized way. The A&M Records' lawyers had incontestable evidence showing the defendant's role in facilitating copyright infringement, for clients depended on servers to talked to other clients. After Napster's demise, other P2P applications using newer, more efficient P2P protocols found their place in this industry. Popular programs like KaZaa (FastTrack protocol), eMule (eMule 2000 protocol), Limewire (Gnutella protocol) employed more decentralized and more structured ways of data exchange. These iterations of the original design, thus in a sense, are considered true peer-to-peer technologies.

Torrent networks: Torrent indexers, trackers & clients

Highlights: ThePirateBay, MiniNova, µTorrent, Azureus

The Torrent network is another file sharing alternative. BitTorrent was developed by programmer Bram Cohen during the summer of 2001. [3] The main quality that sets BitTorrent apart from other P2P technologies is its ability to efficiently transfer large amounts of data quickly and efficiently. When a user downloads something via traditional P2P means, most of the data usually comes from a couple of individuals who are sharing the same completed file. Unlike KaZaa, eMule, and LimeWire, all data on the torrent network are broken up into small pieces and simultaneously shared by huge pools of users. Each individual's Torrent client has the ability to connect to hundreds of other clients who are sharing pieces of the same sought after file. The relationship between clients are symbiotic. In order for computers to download pieces of a file, they too have to share similar pieces with other computers. This forced reciprocity and piece-wise sharing technique provides noticeable boosts productivity and speed. A 2004 report from CacheLogic claimed "Online movie trading is skyrocketing, but onetime leader Kazaa is tumbling in use" Andrew Parker, CacheLogic's founder and chief technology officer said, "The overall level of file sharing has increased. Users have migrated from Kazaa onto BitTorrent." [4] Because computer users are increasingly downloading larger files like movies and software, in the first few years of this decade, P2P traffic on the internet surpassed all other types of data. [5]

There are three integral components of the Torrent system; each provides a specific function that is uniquely independent of the others. Torrent indexers like ThePirateBay and Mininova stores databases full of ".torrent" files which contain the locations of both public and private torrent trackers. These tracker servers help client computers loaded with compatible torrent programs like µTorrent and Azureus connect with other candidates from all across the web. While anyone can download from public trackers, there are exclusive invite-only private trackers that provide even faster connections. Clients act as individual nodes on the network; their main job is to communicate with other clients to trade copied pieces of the requested file until all the pieces are downloaded. An user commences a download by loading a small ".torrent" file retrieved from a torrent index site into the torrent client. The client then communicates to the given server(s) and retrieves a list of IP addresses where pieces of the same file are being hosted. In case a server is down or not responding, clients also have the ability to use DHT (Distributed Hash Table) and PE (Peer Exchange) technology to find the locations of other clients without the assistance of trackers.

Warez networks

Highlights: Astalavista.box.sk, Cracks.ms

Warez is technical slang that stands for a broad spectrum of online counterfeit content. Ripped computer programs, music, movies, books and any copyrighted content published in a organized but illegal fashion can be considered Warez. Underground organizations called "release groups" operate on a minute by minute basis in constant search for new, unreleased music albums and features film to push on the web. In a 2005 Wired Magazine article, Erik Malinowski describes the five step "trickle-down file-sharing" system. [6] He divides up the piracy chain into the insider, the packager, the distributor, the couriers, and the public. According to Malinowski, majority of the high quality content that reaches the internet prematurely originate from insiders. Appointed screeners, workers at optical disk manufacturing plants, and moles within the production industry feed unreleased copies of albums, films, or computer programs to these release groups. In return, these people are usually provided with monetary contributions and access to terabytes of high quality media stored on the release groups' servers. Once a copy of unreleased media content gets into a release group, packagers working non-stop to encode and compress the content into smaller sized, easily transferable files. The content is then stamped with the release group's name or logo, zipped with a NFO file or (information file) giving credit to a release group, and passed on to the distributor. On the digital end, most release groups have relationships with "topsites" or "highly secretive sites on the top of the online distribution pyramid." [7] When a topsite operator publicizes the file on its networks, couriers immediately begin pushing the package to more accessible P2P and Torrent networks for the public to access. On the physical end, release groups can simultaneously sell copies of unreleased content to disc piracy manufacturers all around the globe. Immediately, people in the counterfeit disc business will begin mass producing copied CDs/DVDs to sell to audiences on the streets.

Even though most insiders and people associated with release groups do not know their acquaintances in person, members of these select organizations develop strong bonds with each other, for getting a new piece of media into the public takes teamwork and precision. The race to be first at offering the latest copyrighted content stirs up immense amounts of competition among release groups. Once a copy of an publicly unavailable content reaches the web, the value of such file or files drops close to zero. Over the years these underground networks of moes, hackers, crackers, and rippers were dubbed "The Scene." [8]

Besides producing ripped films and other media, release groups also have been known for cracking licensed software. Instead of insiders, the these groups depend on software crackers to supply the goods. Reverse engineering programmers spend their days trying to figure out how to defeat embedded license protection mechanisms. Crack/CD-key aggregators like Astalavista and Cracks.ms store hundreds upon thousands of key generators, patches, and other forms of cracks for a wide range of software. Users who can't find a prepackaged release from BitTorrent often resort to this manual search method. Though, one must wade through a lot of pornographic content, spyware exploits, and virus ridden files before finding anything useful. For amateur computer users, the risk of endangering their computers' integrity by exposing them to these malicious sites is too great; thus, they turn to traditional legal means.

Web mediums: Media sharing & aggregation

Highlights: Tv-Links.co.uk, PeekVid, YouTube, Veoh

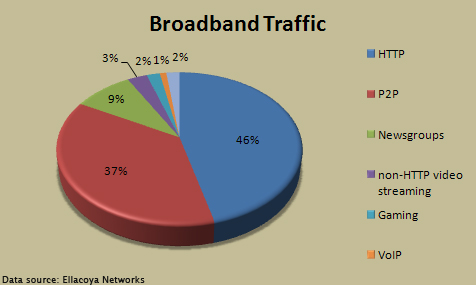

With help from YouTube, online video sharing and streaming websites have caught on as top accessed online services among mainstream internet users. The analysis of internet traffic has always been a great way to measure the popularity of different protocols. For example, typical web browsing will amount to HTTP traffic. (When browsing the internet, notice websites usually have the letters âHTTPâ in front of the URLs.) Likewise, accessing FTP servers will generate FTP traffic, using P2P networks such as KaZaa or BitTorrent will generate P2P traffic, and so forth. For the first few years of the twentieth century, P2P data has dwarfed other forms of transferred traffic largely due to the immense popularity of music and video sharing. In a 2007 study, however, Ellacoya found âfor the first time in four years, P2P traffic finally fell behind HTTP. Chalk it up to YouTube and other Internet video sharing sites. The surge in HTTP traffic is largely a surge in the use of streaming media, mostly video.â Specializing in IP service control, Elacoya said, âBreaking down the HTTP traffic, only 45 percent is used to pull down traditional web pages with text and images. The rest is mostly made up of streaming video (36 percent) and streaming audio (five percent). YouTube alone has grown so big that it now accounts for 20 percent of all HTTP traffic, or more than half of all HTTP streaming video." [9]

YouTubeâs popularity comes with a cost. "New web sites are making it even easier for anyone who can click a mouse to access copyrighted content across the net. You no longer need to know your way around IRC or understand what a .torrent file is. Instead you can just stream them over any number of social video sites." [10] Since there are little to no physical restrictions that prevent users from uploading copyrighted content, individuals often times believe sharing an episode of Family Guy or Friends on YouTube is just. While some companies like CBS allow segments of their popular shows to be streamed online as means of free advertising, other TV stations and media networks retaliated in full force, taking Google's YouTube and Google Video to court. Since the start of the lawsuits two years ago, Google has "agreed to remove more than 100,000 video clips produced by Viacom properties, including MTV Networks, Comedy Central, BET and VH-1, according to a YouTube statement." [11] Of course without an extensive filtering system, people often find ways to sneak copyrighted content onto these services. A recent report titled "Is Google Promoting Video Piracy?" form the NLPC (National Legal and Policy Center) found "Google Video hosted apparently pirated copies of current major films as "Sicko" and "Evan Almighty." Both were posted without the permission or knowledge of the copyright owners. This follows a lawsuit against Google by media giant Viacom seeking $1 Billion in damages." [12] As of June 12th, 2007, Google is preparing to test it's video screen technology that will hopefully flag potential copyrighted material once they are uploaded. [13]

Other online video hosting companies like Veoh, VideoEgg, DailyMotion, GoFish are also stepping up their anti-piracy awareness in fear of lawsuits. Because of this, pieces of copyrighted content are scattered in random locations across the net. Video aggregation sites like the infamous PeekVid and recently popular TV-Links.co.uk compile these hard to find links into one location. In return for these services, these webmasters earn revenue from the pervasive amount of advertisements on their websites.

Conventional means: FTP, Webservers, IRC, USENET

Owners of web and FTP servers have the ability to publish copyrighted content accessible by the internet audience. Since most of these servers are rented by individuals for personal or small business use, these methods of distribution are much slower than dedicated file hosts such as YouSendIt. If something popular is discovered to be hosted on a non-password protected server, the surge in bandwidth during a short period of time can easily cause a system crash. Most of these uploaded copyrighted content stored for either backup or limited sharing among known relations. Unfortunately, search bots or page crawlers such as Googlebot, frequently indexes pages containing these files. There are certain searches techniques one can use to pull up copyrighted content such as songs, movies, or TV shows. Using IRC (Instant Relay Chat) Channels and USENETs to acquire copyrighted content still can be done, but definitely have fallen below main stream usage. Even though both methodologies prove to be extremely fast ways to download files, both require above average computer know-how and connections within online communities that share such content.

|

|

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Every copyable form of media, from mass printing back in the 15th century to the cassette tape technology in the second half of the 20th century, was illegally exploited for profit. Before the popularization of digital formats and the increased accessibility of the internet, illegal distribution of physical copyrighted material was the prevalent form of piracy. Today's global physical piracy can be categorized into three sections: individual license violation, corporate to end-user violation, and reseller/distributor violation.

Individual license violation

The simplest form of physical piracy is committed by the everyday computer user. Factoring intentionality out of the equation, these transactions involve little to no net profit and is pertinent to all kinds of media. People who do not understand or do not care to understand licensing for a specific media product oftentimes overuse or misuse their given rights. Of course, different forms of media have different user agreements. A list of things one can and cannot do with a purchased DVD differs from what one agrees to when installing a computer program. True, some of these rights are innate. The ability to watch a DVD or start Microsoft Word whenever you want comes without question prepackaged in the original deal. After all, one is paying money for ownership.

Many restrictions concerning duplication and distribution, however, are not explicitly outlined in the perplexing user agreements. For example, installing single copy of a popular software on multiple computers is a perfect example of license overuse. The SIAA dubbed this behavior "softlifting." [14] Other forms of manipulative techniques for personal financial benefit are listed as follows. Falsifying one's identity to obtain additional upgrade features or manufacturer discounts, using academic or non-retail software for commercial purposes, copying/distributing licensed software and locked media with immediate relations are all considered individual license piracy. Because these interactions are on a local level, authorities rarely bother to trace this form of physical piracy.

Camcording is a huge issue the movie industry has to face on a daily basis. The term refers to the process where individuals capture featured films with portable recording devices. According to the MPAA, "ninety percent of pirated copies of movies are still playing in theaters. Once a camcorded copy is made, illegal movies often appear online within hours or days of a movie premiere." [15] Recently, stronger legislation have been put in place to discourage people from committing this crime. President Bush in 2005 signed the Family Entertainment and Copyright Act into law. It "makes camcording in a theater a federal felony and establishes new penalties for pirating works that have not yet been released commercially. First-time violators can be sentenced from up to three and five years in prison, and fined up to $250,000 for these kinds of crimes." [16] While some of the amateur camcorder pirates keep these recordings for at home viewing pleasure, most confront the risk for profit or other forms of personal gain. As mentioned before in a previous section, if the moles inside the movie industry do not leak the screener before a specific movie hits theaters, the release groups than depend solely on these lower quality camcorder versions to publish on the internet. These pirates also sell these recordings to "illicit source labs where they are illegally duplicated, packaged and prepared for sale on the black market, then distributed to bootleg dealers across the country and overseas. Consequently, the film appears in street markets around the world just days after the US theatrical release and well before its international debut." [17] In this case, these camcorder pirates can also be categorized in the reseller/distributer group because they are also a vital part of that physical piracy chain.

Corporate to end-user

Corporate to end-user piracy involves the misuse of software licensing within businesses and other organizations, such as schools, universities, and government funded programs. Unlike individual license piracy, the misuse of software licenses in this case are backed by the administrations representing these respective institutions. In the process of increasing productivity by installing better software while keeping costs to a minimum, the higher ups sometimes overlook the obvious legality issues behind allowing the proliferation of intangible things like computer programs.

There are three main forms of corporate piracy. The first form involves installing single-licensed software on multiple computers. Like individual license overuse, when company IT departments hands out free copies of Office 2007 or Adobe Photoshop to their employees, the end-users are benefiting at the loss of Microsoft and Adobe. Many organizations chose to buy volume licensing for expensive software titles. Because it is fiscally inefficient to purchase a copy of software for every single employee, companies oftentimes use keyed servers & keyed programs to reduce costs. This way, only a set amount of licenses needs to be bought for a bigger pool of users; however, thanks to the management of the keyserver, only that set number of users can access this program at any given time. Client-server overuse occurs when this keyserver fails to control the number of people who can access a program at the same time. Finally, hard-disk loading means illegally installing licensed software on computers' hard drives before they are given to employees or sold to costumers. Again, in this case, the end-user is put in a situation where they are unaware that their usage of certain computer programs is unlawful.

Because corporate to end-user piracy improves profit margins (or increases losses from the perspective of the programmers) at a much larger scale than the illegal individual sharing of copyrighted content, the software companies have more incentives to seek compensations. Anti-piracy organizations specializing in hunting down software pirates such as the SIIA (Software & Information Industry Association) and the BSA (Business Software Alliance) have been assisting today's most prominent software companies like Apple, Microsoft, and Adobe fight this and other types of piracy for quite some time now. While both the SIIA and BSA publish reports concerning the latest piracy statistics worldwide, the SIIA even has elaborate online form for company whistle-blowers to report the misuse of software licensing within their organizations. There is even a up to $1 million reward depending on how the pervasiveness of piracy. [18]

Reseller and distributor

Over a period of 18 months, LEK surveyed 20,600 movie consumers from 22 countries and found "62 percent of the $6.1 billion loss (reported by the movie industry) result from piracy of hard goods such as DVDs, 38 percent from internet piracy." [19] Despite recent telecommunication advances and increasing numbers of broadband computer users, compared to online digital piracy, physical piracy still plays a larger role in the global piracy market. The reason for this phenomenon is largely due to the well built infrastructure and well engraved ideologies in select regions of the world. People in countries like Armenia, Moldova, and Azerbaijan, where over 90% of the software are obtained illegally, do not believe in paying for software. [20] Lifetime habits, after all, are hard to change. Of course, larger piracy-ridden countries like China, India, and most of Southeast Asia also play huge roles in fostering the continual growth of this illegal act. Resellers and distributors of copyrighted material contribute to the largest portion of today's worldwide physical piracy.

Unlike corporate and individual piracy, resellers and distributors work in closely knit, well built networks of sellers and buyers, all of whom have the ultimate profit seeking goal in mind. In a way, these collections of physical pirates analogous to the previously discussed online release groups. With speed and style in mind, these people deliver top notch replications of the latest unreleased content in a matter of hours after something is leaked. Reseller and distributor physical piracy can apply to all different forms of media. From software to movies, from music to games, all digitally formatted content have the risk of being physically copied and sold. Selling copied or counterfeit software for a reduced price as street vendors or in counterfeit stores, running unlicensed movie theaters or rental facilities, illegal direct resell and auctions of improperly licensed media are all considered physical piracy.

Case Study #1: What is wrong with this picture?

In this eBay auction, the seller is attempting to sell a valid Windows OEM license. He states in the description of the auction "the computer died but your winning bid the license can live on. Since the original system died, this Windows XP Home Edition license can be activated on another system. This is an auction for one license key only. No software is included. It is branded Toshiba but will work on any system. You may need to call Microsoft's 800 number to activate." Whether or not the seller made a genuine offer is besides the fact, for when one posts the a readable picture of the serial number, what is there left to "purchase"? $39.95 is a heavy price to pay when one can just copy down the number. Surprisingly, there were 12 bids on this auction when this screen shot was taken.

|

|

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

By understanding methodologies behind these commonly used utilities and practices, we can have a better understanding of piracy's role in the lives of digital natives.